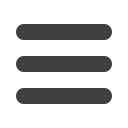

146

|

World Gold Coins

H

IGHLY

I

MPORTANT

T

RANSITIONAL

P

ATTERN

G

OLD

B

ROAD

B

Y

S

IMON

Thomas Simon, born circa 1623, was one of the sons of Peter Simon of Guernsey, whose older brother, Abraham, was also a medallist. He

first came to the attention of Nicholas Briot about 1635 and was engaged as an apprentice at the Royal Mint, his first work being the "Scottish

Rebellion" medal of 1639. As was the rule of the day, he also worked as a gem-engraver. His talents caused him to be appointed joint-

engraver to the mint in 1645, just as the Civil War was changing England' s greatest traditions. In 1648, he was authorized to engrave the

Great Seal of the Commonwealth, and then in 1651 he engraved the new Great Seal of England, showing not a king' s image but instead an

intricately detailed map of England and Ireland on its obverse and, opposite it, a portrayal of Parliament assembled without a monarch. The

surrounding legend on this piece proclaimed "1651 IN THE THIRD YEARE OF FREEDOME BY GODS BLESSING RESTORED." This sentiment

surely enraged royalists, but in fact Thomas Simon only did as he was ordered, as an employee of the mint. During the Commonwealth, he

mostly engraved seals and medals, and was politically neutral.

Simon came to Cromwell' s attention immediately after the defeat of the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar (September 3, 1650), a great victory

for the Commonwealth army. Simon' s talent caused him to be ordered to make effigies of General Cromwell, to be used to strike gold and sil-

ver medals as awards to officers and soldiers who took part in the battle. This work was so well received that Simon was next selected to

engrave dies for Cromwell' s coins, struck from 1656 to 1658, the pieces that were so stunning compared to the coins made by hammer. One

feature of Cromwell' s coins that had never appeared before on any English coin was the cameo effect created by the frosted texture given to

the portrait, and importantly this appears on our gold pattern of 1660 as well. Forrer' s Biographical Dictionary of Medallists (volume 5, page

521) quotes an earlier source, Lee' s Dictionary of National Biography, which stated that "The frosting observable on these coins appears to

have been introduced by Simon."

But Simon' s immense talent would not serve him ably enough during the Restoration. Thomas Rawlins was reinstated as chief engraver at

the mint. In June 1660 he was ordered to prepare a new portrait of the king, but failed to do so on time, and Simon was given the assignment

on August 10 of that year. His portrait was highly regarded but the hammering technique failed to produce coins that met with the mint' s

approval. His work, however, was so well appreciated that he was given the job of engraving dies for all the new milled coinage. Then came

the fateful contest between him and John Roettier, of Flanders, in February 1662. Simon produced the magnificent and now famous Petition

Crown, with its stunning royal image and the spectacular edge engraving that petitioned King Charles II to select Simon' s work for the royal

coinage. Perhaps remembering Simon' s medal of 1651, the king himself decided in favor of Roettier, effectively ending Simon' s employment

at the Royal Mint. He died of the plague in June 1665.

Numismatics is an intriguing science, however, and research provides another explanation for Simon' s demise. Challis responded to the tradi-

tional view that the king' s bias caused Simon' s talents to be rejected. A New History of the Royal Mint (pages 349-350) discusses the quality

of the puncheons and other minting tools used to produce coins. Challis notes that while Simon' s dies were splendid he "had demonstrated

his inability to produce dies which would withstand the press" with its intense pressure, and in particular this was seen in puncheons that he

produced for the Goldsmiths' Company of London, which annually contracted with him to make a set of three puncheons showing the com-

pany' s mark, which included a facing leopard' s head. In the early 1660s, Challis continues, "Simon' s puncheons simply would not withstand

normal use." In the end, it was all about economy. Simon blamed the rejection on the poor quality of the silver to which his puncheons were

applied by the company, but "the real trouble lay in the inadequacy of the metal from which they were made." And here is the conclusion: "If

such an explanation is correct it seems likely that it contains the key to why Simon, regarded by many from his own day to this as one of the

finest engravers the Mint has ever had, lost out in the competition with the Roettiers. It was not that Simon was hopelessly disadvantaged at

Court by his having willingly served the Protectorate. Rather it was that he could not match the Roettiers in being able to produce dies which,

day in day out, would withstand machine production."

To our knowledge, it has not been pointed out before that, on this magnificent pattern, a work of art struck in gold, Thomas Simon placed the

Goldsmiths' Company' s mark, the face of a leopard, at the base of the king' s throat, peering at the world in a silent petition to "remember

me" centuries after King Charles and all his contemporaries perished - perhaps another artistic way of saying Magnalia Dei!

Estimated Value ..................................................................................................................................................................$125,000-UP