145

bid online at

www.goldbergcoins.com(800) 978-COIN (2646)

|

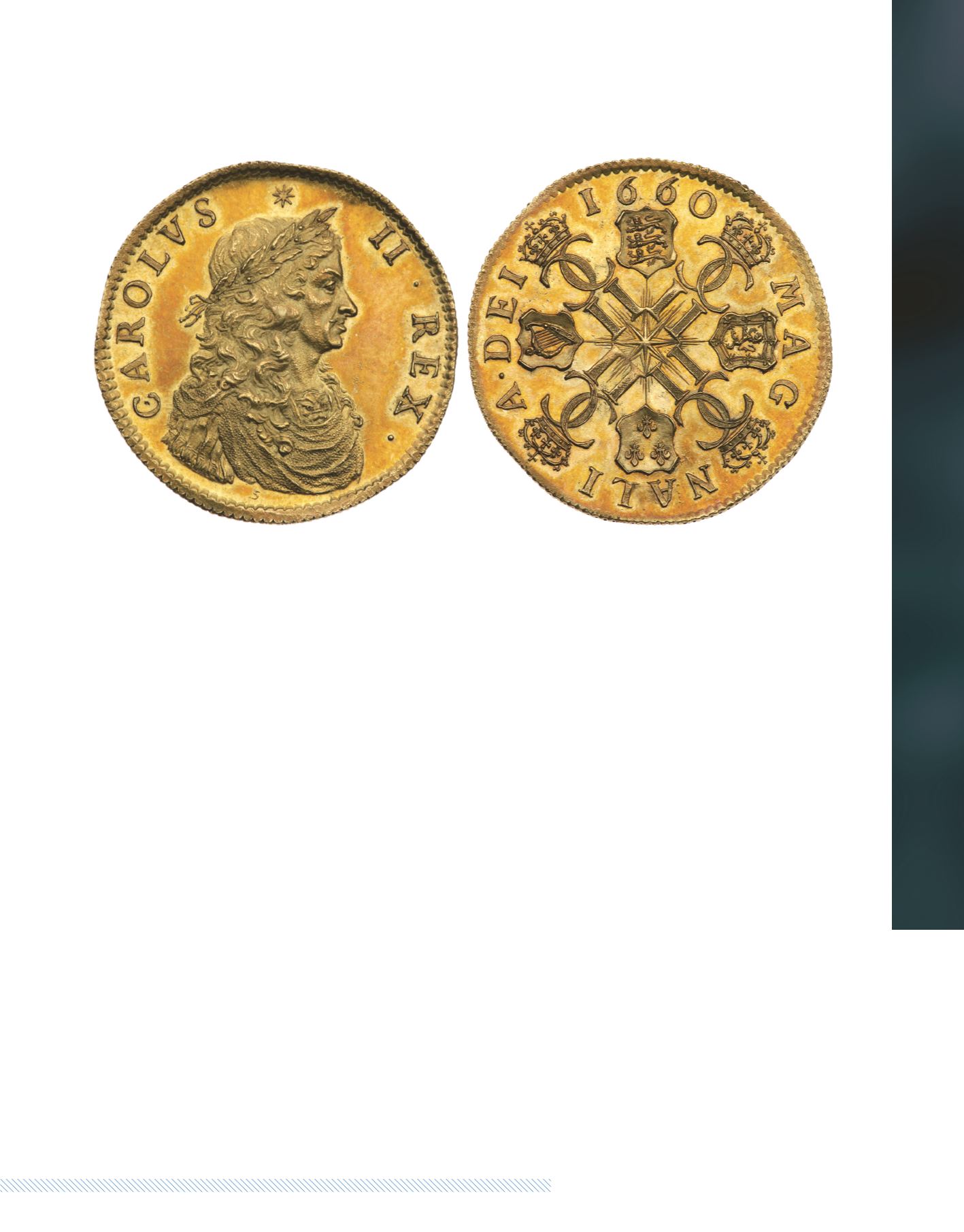

Great Britain. Charles II pattern gold Broad, 1660

. North-2777, Montagu-818 (Sotheby, London, November 1896), KM-Pn30. By

Thomas Simon. Reeded Edge, signed "S" beneath the portrait, 30 mm, The stunning reverse legend MAGNALIA DEI translates to mean

"The Mighty Acts of God." An astonishingly well-preserved specimen, likely finest known, and of numismatic importance as a gold pattern

of similar statue to the famed Petition Crown struck in silver. The collecting opportunity of a lifetime to acquire this historically significant

and beautifully made coin!

PCGS graded Proof 63+ (Heavy Cameo not noted on grading insert)

.

When Prince Charles landed at Dover on May 25, 1660, he knelt down and kissed the English soil. It was far more than a merely symbolic

gesture. It was a singular event in English history, the moment that set in motion the restoration of the monarchy throughout the land. A

month before, Parliament had resolved to proclaim him King Charles II so long as he adhered to the Declaration of Breda pardoning many

of his father' s enemies and relinquishing the historical, absolute powers of the monarchy. He arrived in London four days later, on his 30th

birthday.

There was a great deal to forgive. When he was 18 years old, his father had been beheaded for "treason" in the winter of 1649. He was

the only surviving son of his parents, natural heir to the Court of St. James. That right evaporated upon his father' s execution. As a teen-

ager, he had accompanied his father during the late campaigns of the Civil War, and had witnessed the end coming. Charles and his

mother, Queen Henrietta Maria, had been exiled in 1646 to France and protected by his first cousin, King Louis XIV, during the final years

of the war, and all during the Commonwealth and then the disastrous reign of Oliver Cromwell. When Cromwell died, his son, Richard, had

shown himself to be feckless. The nation stood in ruins. Cromwell had crushed royalist supporters but Charles II pardoned many who had

ransacked the country, only taking revenge on a few dozen of Cromwell' s most offensive military and legal supporters.

Charles II was the first of a new breed of monarchs, and much of his passion was devoted to the arts despite the catastrophes of the first

years of his reign, including the plague and the Great Fire of London, as well as external wars. He began building what eventually became

the royal art collection of paintings, and he was a magnanimous patron of the flourishing sciences as well as of architects such as Christo-

pher Wren. He took a particular personal interest in sculpture and in the engraving arts as well, to which the superb artistry of his wonder-

ful pattern attests, for it was a departure from the medieval style of engraving that had been stereotyped in its lifeless style and flat

imagery. Here, instead, we see a lifelike image of the king replete with touching details shown in considerable relief and with artistic flair.

The fabulous work of engraving art seen in this lot, struck only as a pattern, was largely responsible for the introduction of the "milled," or

machine-made, coinage as ordered by the King in Council on May 17, 1661, shortly after this piece was created. As the king is known to

have taken a personal interest in his effigy, he may well have inspected this very coin, and it is known from contemporary sources that

using Simon' s superbly engraved dies to make the hammered coins drew considerable dismay from the mint itself: hammering the dies

could not bring up the details that distinguished the die-work. It is plausible that this pattern stood as proof that hammering was obsolete

as a minting technique.

The short-lived milled coinage using Simon' s effigy of Oliver Cromwell and his shield, and struck by Blondeau, ended in August 1660 with

removal from the mint of the milled machinery, no doubt partially as a result of jealousy by mint employees fearful of losing their positions

as hammered workmen but also in response to the use of that machinery during the hated reign of Cromwell. Cromwell' s coins, however,

showed that the hammering technique was old fashioned and unable to forestall counterfeiting and the illegal shaving of metal from the

uneven edges. A sea-change was in the works.

cont’d next page

H

IGHLY

I

MPORTANT

T

RANSITIONAL

P

ATTERN

G

OLD

B

ROAD

B

Y

S

IMON

2285

Enlargement