73

|

Session Five - Tuesday, February 14th 10:00am PST

A

WESOME

C

RETAN

T

ETRADRACHM

D

EPECTING

C

OMPLETE

L

ABYRINTH ON

R

EVERSE

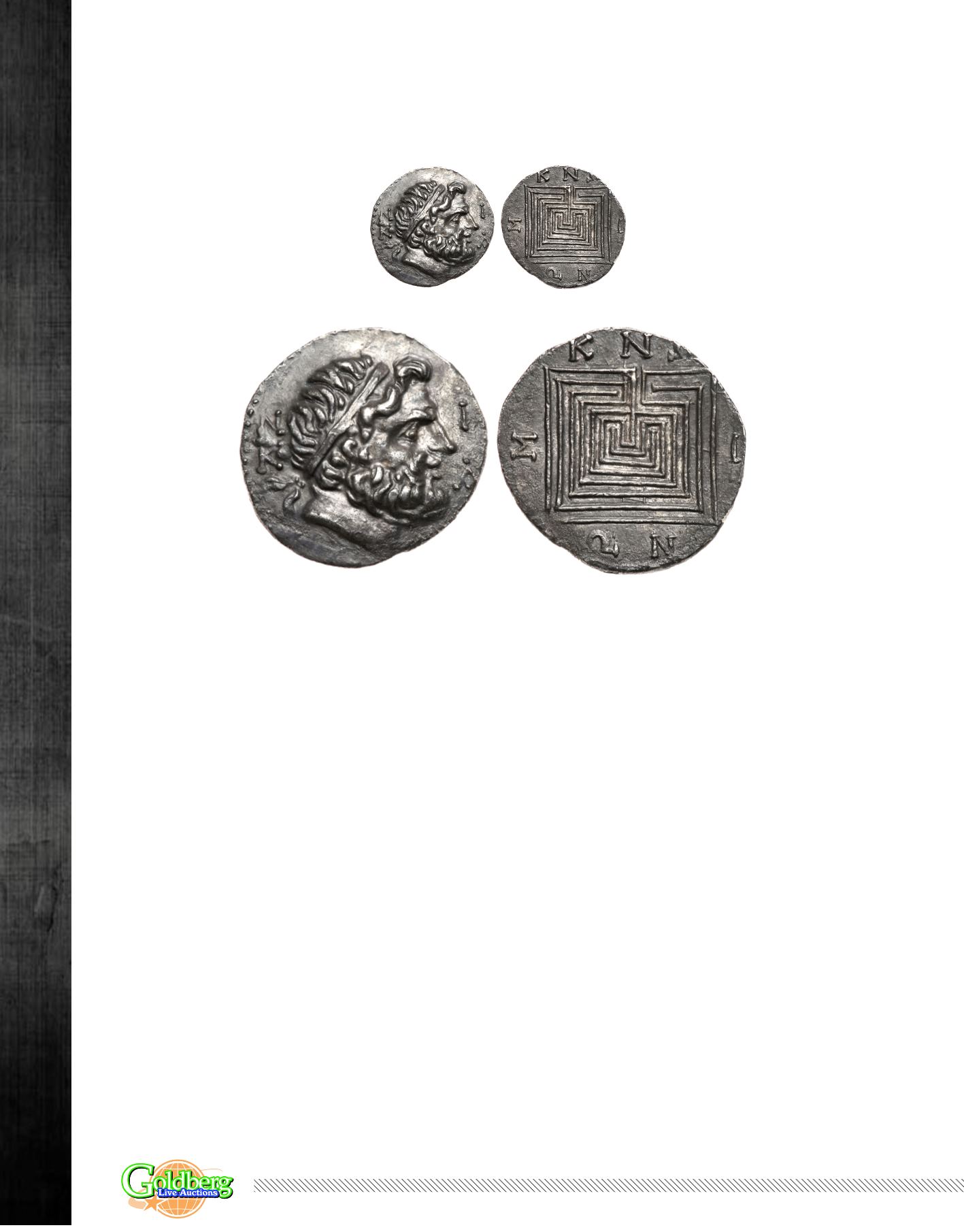

1676 Crete, Knossos. Silver Tetradrachm (15.39 g), ca. 200-67 BC

. N-I/K-A in two lines, laureate head of Zeus right.

Reverse:

KN

/

-I/

N in

three lines, labyrinth. Svoronos 177; SNG Lockett 2543 = Pozzi 4403 (this coin); SNG Copenhagen 381.

Very Rare and probably the finest

example in existence!

Boldly struck and perfectly centered on a nice broad flan. Uniform dark tone.

Superb Extremely Fine

.

Estimate Value ......................................................................................................................................................................... $10,000 - UP

The Hanbery Collection; Purchased privately from F. Kovacs in the 1980s. Ex Richard Cyril Lockett Collection, pt. III (Glendining' s, 27 May 1959),

2019; Ex Prof. S. Pozzi Collection (Naville I, 4 April 1921), 1971.

Knossos was renowned in antiquity as the Cretan capital of King Minos, who mythographers and historians like Thucydides considered to have

ruled the first thalassocracy (naval empire). Despite his great power - which at one time extended over Athens on the Greek mainland - his family

was cursed by the gods. His wife, Pasiphaë, became smitten with a majestic bull and employed Daidalos, Minos' great engineer, to build a wooden

cow device so that she could consummate her unnatural lust for the animal. The result of this coupling was the monstrous minotaur, a bloodthirsty

half-man and half-bull creature.

Unwilling or unable to destroy this monstrous offspring, Minos ordered Daidalos to construct a winding maze that was so difficult to navigate that

the Minotaur could be safely kept a prisoner inside. Daidalos, with the help of his son Ikaros, followed his king' s command and built the famous

Labyrinth, which is depicted on the reverse of this coin and which may derive its name from labrys, the double-headed axe that appears to have

had an important ritual function in Bronze Age Crete.

Unfortunately for the two builders, once the Labyrinth was complete, Minos had them shut up inside in order to prevent them from ever divulging

its secrets to the outside world. The wily Daidalos, however, used wax and bird feathers to construct artificial wings for his son and himself so that

they could escape by flying out of the unroofed maze. The plan worked perfectly until Ikaros flew too close to the sun and the wax of his wings

melted, causing him to fall to his death in the sea off the coast of southwestern Asia Minor, which thereafter was known as the Ikarian Sea.

Despite the escape of Daidalos and the tragic death of his son, the Labyrinth still stood and housed an increasingly hungry and angry Minotaur. In

order to satisfy the monster' s need for human flesh, Minos demanded tribute from Athens in the form of seven youths and seven maidens every

seven or nine years. After this horror had taken place twice, the Athenian prince Theseus volunteered to serve as one of the youths in order to go

to the Labyrinth of Knossos in the hope of slaying the monster and ending the bloody tribute. With the help of Minos' daughter, Ariadne, he

marked his path in the maze by unwinding a ball of yarn so that after killing the Minotaur he could retrace his steps and safely exit the Labyrinth.

Thus the great mythological fame of Daidalos' maze and Theseus' destruction of its inmate made it the perfect civic badge for the coins of Knossos

in the early Hellenistic period.

Enlargement