of the young heir, Gaius Caesar, the eldest son of Augustus’ lieutenant M. Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder, whom Augustus

adopted that year along with his younger brother, Lucius. The first interpretation rests on the oak-wreath surrounding the portrait,

identifying it as the

corona civica aurea

which in 28 BC was awarded by a grateful Roman Senate to Augustus for having ended

the long period of civil wars, and accordingly positively identifies the portrait as being that of Augustus. However, no convincing

argument explains why his portrait would be rejuvenated. R. Prideaux recently put forth the idea that the issue was struck at a special

military mint operating in Pannonia in 12 BC to appease Agrippa’s troops after his untimely death while on campaign in Pannonia

in that year, and that the portrait was engraved by someone unfamiliar with the emperor’s likeness (see the commentary to Triton

XI, 829). This argument fails on two counts: firstly, an engraver with the legions in Pannonia would most certainly be familiar with

the portrait of Augustus as the troops were paid in denarii transported from the main imperial mints, and secondly, legions would

not simply begin striking coins on their own initiative because to do so would be a treasonous usurpation of an imperial prerogative.

Although not addressed in the Triton commentary, Prideaux also mentions the funereal importance of the candelabrum on the

reverse. Rams’ heads are fairly common adornments on Julio-Claudian funerary altars (see, e.g., P. Zanker,

The Power of Images in

the Age of Augustus

p. 280 for a Roman funerary altar of the Claudian period that features the garland, candelabra and rams’ heads),

and an aromatic garland was a staple of Roman funerary rites for obvious reasons. Otherwise the association of the candelabrum

with the

ludes Saeculares

(which is the traditional interpretation of the type) is not readily apparent. Seemingly only a death of

significance to the succession would manifest itself on coinage, and the death of Agrippa in 12 BC was one such death as he was not

only Augustus’ closest friend and confidant but his chosen successor. It is recorded that the emperor mourned his passing for a full

month and even had Agrippa’s remains interred in his own mausoleum despite Agrippa having constructed a mausoleum of his own.

In light of the funerary nature of the reverse of this coin, and also the fact that nothing specifically ties it to the

ludes Saeculares

of

17 BC other than the tenuous link of the candelabrum reverse, could it be that the portrait in the obverse is in fact young Gaius

Caesar and that it was struck in 12 BC to commemorate both Agrippa’s death and Gaius’ newfound role as Augustus’ direct heir?

The framing

corona civica

would quite nicely associate the youth with the

imperium

of the principate in this instance and should not

necessarily be interpreted as a prerogative solely of the emperor. It also serves as an artistic function as a balance to the floral border

enclosing the candelabrum on the reverse. Furthermore, as David Sear notes in the millennial edition of

Roman Coins and Their

Values,

the combination of the youthful portrait along with the title CAESAR simply and clearly suggests the young heir, while its

placement in the place of precedence on the obverse further serves to highlight his status.

1186

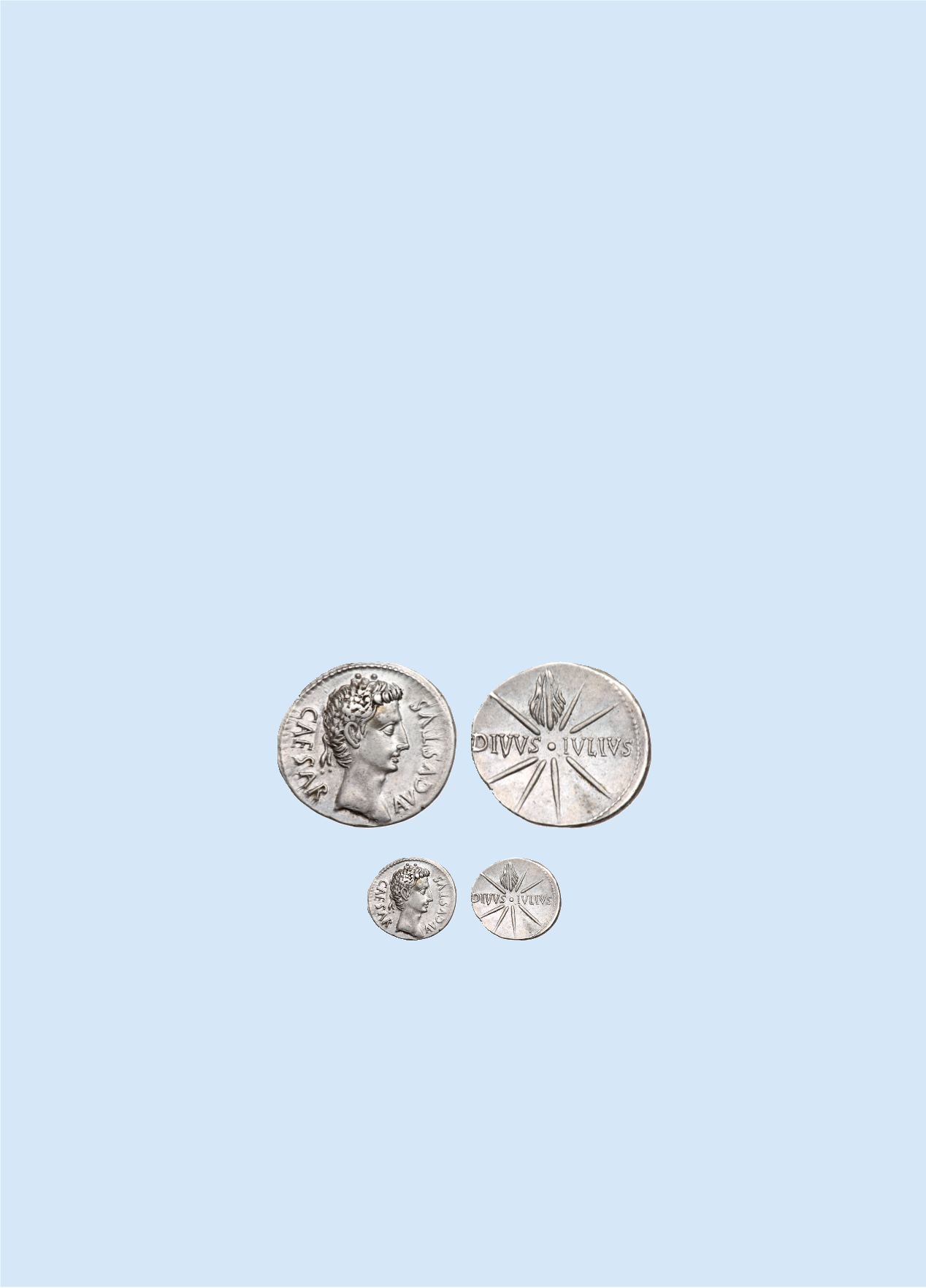

Augustus. Silver Denarius (3.69 g), 27 BC-AD 14. Tarraco(?), ca. 18 BC. CAESAR AVGVSTVS,

laureate head of Augustus right. Rev. DIVVS IVLIVS, comet with eight rays and tail. (RIC 102 (Colonia

Patricia?); BN p. 196 *, pl. LIV, c; BMC 357; RSC 98). Well struck on a nice full flan. Lightly toned.

Extremely fine.

$ 2,500