29

3040

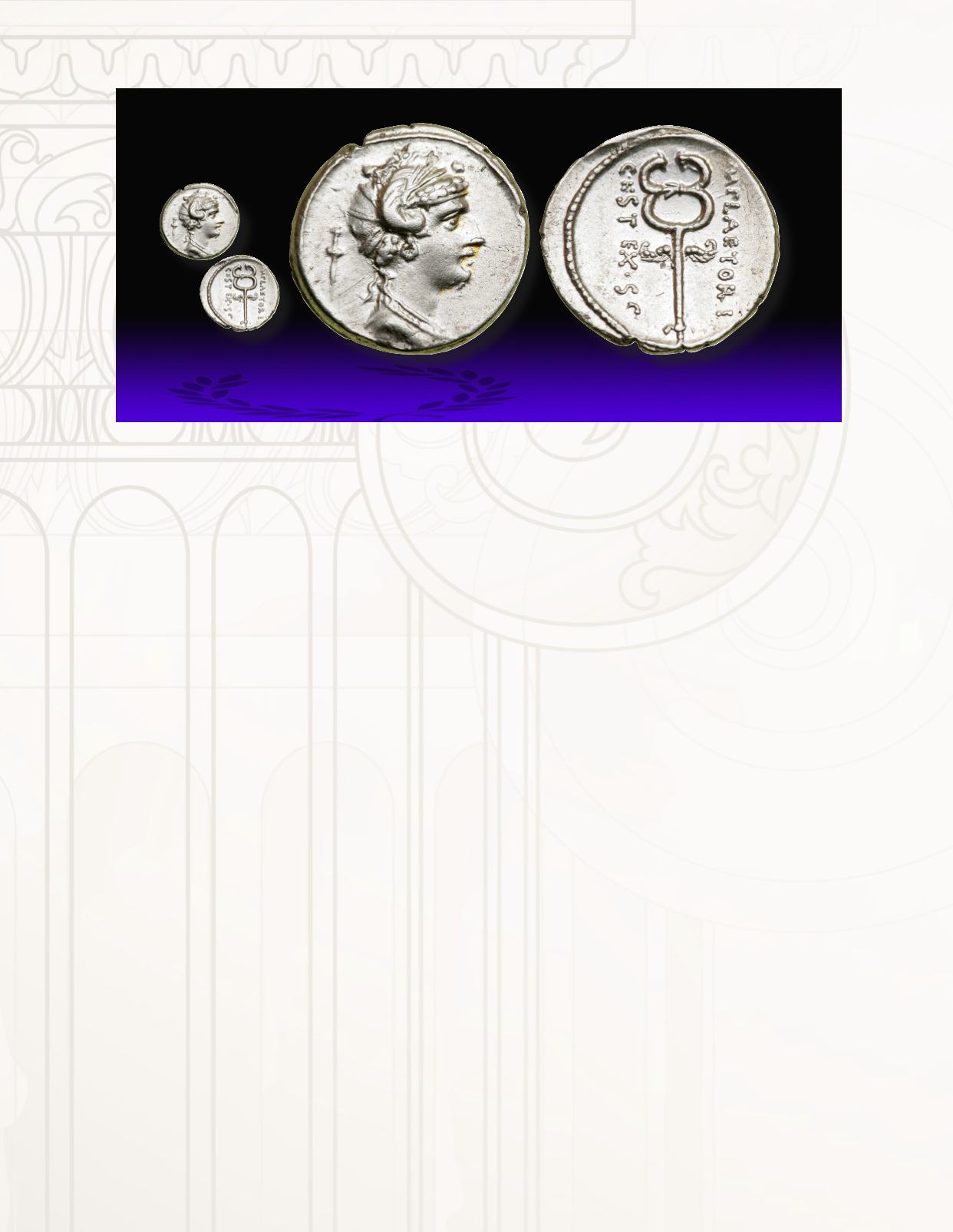

M. Plaetorius M.f. Cestianus. Silver Denarius (3.91 g), 67

BC.

Uncertain mint. Draped female bust right, with hair in bag

or net; behind, dagger.

Reverse:

M PLAETORI CEST EX S C,

winged caduceus. Crawford 405/3b; Sydenham 805; Plaetoria

6. Well struck and nicely centered, lustrous.

Nearly Mint State.

This moneyer’s coinage of seven distinct types falls into two

groups, the first group with two types having the legend AED

CVR EX S C showing that Cestianus struck those coins while

curule aedile in either 68 or 67 BC, and five types that are

special issues authorized by the Senate and employ the leg-

end EX S C (ex senatus consulto). This latter group, from which

this coin comes, was dated by Crawford and others to 67 BC,

but Hersh and Walker reassigned them to 57 BC based on the

fact that the Mesagne hoard contained no examples. How-

ever, the five types in question show marked stylistic differenc-

es, which indicates that each was either struck at a separate

officinae with different workmen involved in engraving the

dies, or, a more reasonable assumption, that they were struck

at different mints altogether. Additionally, all employ control

marks, a feature that saw its heyday in the 70s and early 60s.

In the early 60s BC, there was a significant pirate menace in

the Mediterranean. Rome was at special risk as it imported

most of its food fromoutside of Italy, and the pirates were caus-

ing prices to skyrocket. After previous attempts to confront

the problem had proved ineffectual, legislation was passed

assigning command to combat the pirates to Pompey, giving

him extraordinary command over the entire Mediterranean

Sea. He was allowed to recruit as many troops as he thought

necessary, and he did so, raising 120,000 infantry, 5,000 cav-

alry, and a sizable fleet of 500 ships. The money to pay for

this massive buildup - according to Appian 6000 Attic talents

(24,000,000 denarii) - was authorized by senatorial decree.

Pompey divided his command into thirteen districts, assign-

ing each a fleet under the command of a legate. He kept for

himself a fleet of sixty ships, with which he toured the various

districts. His first efforts were concentrated in the western Med-

iterranean, and in a mere forty days he eliminated the pirate

menace there. He then went on to the eastern Mediterranean

and quickly subdued the remaining pirates, many of whom

had settled in southern AsiaMinor at a distance from the coast.

It is in light of these events that Cestianu’s non-AED CVR

types should be seen. Pompey needed someone familiar

with minting operations to coin the 6000 talents decreed

by the Senate to pay for extraordinary command, and

Cestianus, who had just served as curule aedile with au-

thority to strike coins, fit the mold perfectly. Additionally, it

is logical to assume that he would have traveled through-

out the thirteen districts seeing to the monetary needs

of each fleet, which would explain not only the divergent

styles of his five EX S C types, but their complete absence

from the Mesagne hoard. Finally, this resolves the question

of symbols reappearing on coins in the 50s. For these rea-

sons Cestianus’ non-AED CVR denarii should be assigned a

date of 67 BC, not 57 BC as proposed by Hersh and Walker.

Estimated Value ................................................. $1,000 - 1,400

Gemini V (6 January 2009), 235.